Articles, Case Studies, News, Events

Executive Coaching

A Contextualised Approach to Coaching

The remarkable growth in the popularity of coaching can be explained in part by the dramatic changes in organizations in all sectors of the economy, according to Claire Huffington. For example, there has been extreme turbulence created by the revolution in information technologies and the transmission of knowledge, globalisation of markets and hence competitive pressures, and increasing levels of risk created by these changes—among other factors.

Executive Coaching; systems-psychodynamic perspective, ed.Halina Brunning, 2006, Karnac, Londen / New York.

Setting the Scene

Executive coaching involves a one-to-one relationship between a consultant or coach and a client, usually a senior executive leader or manager, which aims to further the effectiveness of the client in his or her role in the organization.

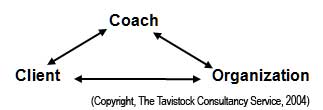

Therefore it is a dyadic task relationship, but with an important difference, for example, from psychotherapy, in that it is a relationship in which there is always an implicit external context in view. This is the organisation in which the client comes, in which he or she works and which pays for the coaching. In other words, in all the exchanges that take place between the client and the coach, there is always a third party in the wings. This ‘third party in the wings’ is present in at least two ways:

- as an internal reality in the mind of the client and the coach, and

- as an external reality out there, to be engaged with or not

Therefore, what the client says or does and what this elicits in the coach, as he or she listens and observes, needs to have reference to this omnipresent, sometimes hidden, third. What I am referring to here is the client and coach’s shared experience of the organization through the client-coach relationship.

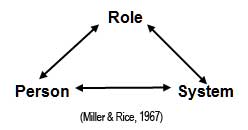

In referring to the coach as a consultant, I am deliberately framing coaching as organizational consultancy delivered through an individual. This is relevant even if one never engages directly with the organization, apart from contractually. It could also be argued that this is the type of consultancy currently acceptable to organizations, or, as one client put it, ‘coaching is the new organisational consultancy’. Indeed, working with individuals in organizations was once termed by consultants trained in the Tavistock tradition as ‘role consultation’ or ‘organizational role consultation’ or ‘organizational role analysis’ (Reed and Bazalgette, 2003). This work quite explicitly addresses the client’s exploration of the interplay between himself or herself as an individual or person, in role in relation to the whole system or organization and seeks to help the client in a leadership role to develop the capacity to think systemically. According to Miller and Rice (1967), the interplay between the individual or person in their role in the organization or system can be represented as in the diagram here. When ‘executive coaching’ began to gather pace as a mode of intervention in organizations, I and colleagues at the Tavistock Consultancy Service1, partly for marketing reasons, began to redescribe role consultation using this label. And indeed, there are close parallels between how we work or worked as role consultants and how we currently work as coaches. There are, however, various respects in which this change of labels has led us to redesign what we do and how; also to bring into view and emphasize certain elements more than others. For example, in role consultation, the emphasis tends to be more on reflection and understanding as ends in themselves rather than on action and outcome; whereas the reverse might be said to be true for coaching, at least as practiced by some in the field. (e.g. Whitmore 1994). Previously we might have worked with a client on helping them to develop a vision for their organization or area of work. Now we might also be inclined to work with them on implementing this vision, setting goals and checking progress towards them. In this respect, it is possible to see coaching as a variety or sub-set of process consultancy (Schein 1988, 1990) focused on work with the individual or a number of individuals in an organization. It may be possible to engage directly with the organization both in order to help the individual and to feed back broader organizational themes that may assist the organization in its development, as well as engage in wider consultancy activities delivered from the launch pad of coaching. Doing so raises a number of dilemmas, which need careful consideration, for example, how to hold individual client confidentiality if one is engaging more widely with the organization2. In this chapter, I will explore some of the conceptual, practical and ethical consequences for coaching of keeping the context in mind in this way. This is what is meant by a contextualised approach to coaching. Then there is a deeper exploration of the conceptual territory covered by the approach from the springboard of the concept of ‘the organisation-in-the-mind’ (Armstrong, 1997) Next, a particular take on the current context in and around organizations is offered as an explanation for the growth in the demand for coaching. This aims to clarify some of the needs coaching seems to be addressing in individuals and organizations and the nature of the coaching response that therefore appears to be required. Lastly, there are examples of way in which the coach can engage directly with the organization and some of the opportunities and dilemmas this can present. THE CONTEXTUAL PERSPECTIVE: THE CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK IN PRACTICE In listening to the client’s story, the coach uses himself or herself ‘rather like a tuning fork – a place of resonance against which data takes on meaning that can be tested or refined and applied to the problem at hand’ (Pogue-White 2001). The coach is not only listening, associating to or tuning in to the ‘person’ of the client in his or her context, but also to the organization conveyed in and through his or her words, silences and feelings. It is this kind of ‘dual listening’

- to the individual in the organization, and

- to the organization in the individual

that one tries always to keep in mind. It is through this dual listening that the nature and implications of the dilemmas, difficulties and challenges the individual is facing his or her role come more clearly into view and can be tested in behaviour3.

If we consider executive coaching to be a variety or subset of organizational consultancy, and bearing in mind the organization as the ‘third party in the wings’ or even in the meeting room, what might this look like in practice? Clients bring concerns and issues that look, sound and feel highly personal as well as those that are more clearly connected to their role in the organization or, more widely, general organizational issues. There could be, in addition, issues that sound more obviously personal or ‘private’ – work/life balance, marital difficulties or personal distress of various kinds. Whilst these ‘personal issues’ can be worked with as individual concerns separate from the organizational context, they can and should also be read – at least initially – organizationally, against an organizational boundary as well as an individual one. Doing so can reveal insights for the client both as an individual and as a member of an organization and, potentially for the organization as a whole. An example of working in this way is described below in order to make this clear.

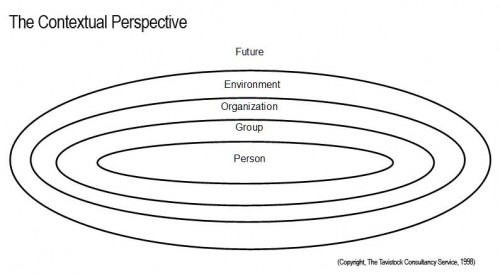

But, before doing so, I would like to expand the idea of organizational context from the person/role/system model mentioned earlier into a series of concentric circles around the individual client, as in the diagram below (click to enlarge):

It is useful to consider the client in relation to a series of interlocking boundaries or hierarchically organized ‘layers of meaning’ (Cronen and Pearce, 1985) against which his or her issues can be understood. For example, in helping to consider a job change, one might explore this in the context of the marketplace and competitive environment around their current organization; or opportunity, or lack of it, in the organization itself; or one might think with the client about whether the desire to leave their current organization is connected to relationships in the immediate work group; or in other more personal ways, for example connected to the stage of professional development reached by the client. Each of these lines of enquiry would create a complex set of meanings for the client to consider, expanding their understanding and future options for changing jobs. The important theme here is not to ‘fall in love and marry’, a particular hypothesis or way of explaining a client’s issue, thus getting stuck in one circle of context, particularly the personal (Campbell, Draper and Huffington 1988, 1989). It is important for the coach to keep alive in his or her mind a range of possibilities and ways of understanding the ‘presenting symptom’ often and increasingly felt as a personal, especially in the individualized and survivalist culture of organizations today (Kilburg, 2002). A good piece of advice is to start thinking as widely as possible, being reluctant to see an issue or concern solely owned by the individual when he or she is coming from an organization to be coached.4

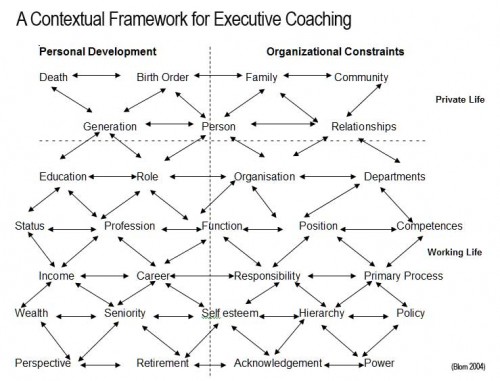

Another, more developed way of thinking about this contextual framework is shown in the diagram below (Blom 2004). This shows a framework that can be used by the coach in working with a client to ensure all relevant potential issues affecting the client’s work performance can be explored. Blom separates personal from organizational issues and ‘private life’ from ‘work life’ issues but shows how the personal/private/work context can be connected. A further conceptualization would be the Six Domains Model presented by Halina Brunning in another chapter of this book.

(click to enlarge)

It is useful to consider the client in relation to a series of interlocking boundaries or hierarchically organized ‘layers of meaning’ (Cronen and Pearce, 1985) against which his or her issues can be understood. For example, in helping to consider a job change, one might explore this in the context of the marketplace and competitive environment around their current organization; or opportunity, or lack of it, in the organization itself; or one might think with the client about whether the desire to leave their current organization is connected to relationships in the immediate work group; or in other more personal ways, for example connected to the stage of professional development reached by the client. Each of these lines of enquiry would create a complex set of meanings for the client to consider, expanding their understanding and future options for changing jobs. The important theme here is not to ‘fall in love and marry’, a particular hypothesis or way of explaining a client’s issue, thus getting stuck in one circle of context, particularly the personal (Campbell, Draper and Huffington 1988, 1989). It is important for the coach to keep alive in his or her mind a range of possibilities and ways of understanding the ‘presenting symptom’ often and increasingly felt as a personal, especially in the individualized and survivalist culture of organizations today (Kilburg, 2002). A good piece of advice is to start thinking as widely as possible, being reluctant to see an issue or concern solely owned by the individual when he or she is coming from an organization to be coached.4

Another, more developed way of thinking about this contextual framework is shown in the diagram below (Blom 2004). This shows a framework that can be used by the coach in working with a client to ensure all relevant potential issues affecting the client’s work performance can be explored. Blom separates personal from organizational issues and ‘private life’ from ‘work life’ issues but shows how the personal/private/work context can be connected. A further conceptualization would be the Six Domains Model presented by Halina Brunning in another chapter of this book.

(click to enlarge)

Case example 15 Nicola, a Vice President in the Operations side of an investment bank, was meeting me for a series of executive coaching sessions. These were built into a leadership development programme for people entering senior management roles for the first time. Soon after we began meeting, she brought for discussion a difficulty that had been pointed out to her by her line manager and about which she was quite distressed; that she was very poor at making presentations and getting her point across in meetings with senior colleagues. It had been suggested to her that she sought presentation skills training to solve her problem, which was seen as personal, but she felt that this was not the whole story and wanted to explore it further with me. It turned out that Nicola thought she was very good at making presentations and asserting herself with her team of 60 people and she also felt she had no difficulties with senior colleagues in the Operations side of the bank. The situations that were difficult were meeting which involved senior colleagues in the Trading part of the bank; and this is where she thought the feedback about poor presentation skills had come from. Traders are the exciting, risk-taking, deal-making part of the bank, whereas Operations is the ‘boring’, back-room part of the bank that processes the deals and takes care of risk management, audit and record keeping. Traders serving a particular financial sector were organized into business units and traders and Operations staff serving that business unit would meet regularly as a team to review business progress. Traders historically tended to see themselves in a lead role in these meetings with operations staff present to react to their requests. Nicola experienced difficulty in the meetings because she and others at her level in Operations were being encouraged to take a strategic and more pro-active approach to the business, especially on issues like risk management and cost reduction. The bank was worried about crisis in the financial world following various dramatic business collapses and lack of confidence in professional dealing with audit and investment. So there were pressures coming from the environment on the bank, which was, as a result, changing the way it conducted its business. It was important for Nicola to be able to use the meeting with traders to point out the risks of taking one particular course of action or another, so that steps could be built in from the start of a venture to counteract any problems. She found it stressful to operate in this new way because traders were used to being in control and having their own head and resented what she felt they experienced as let and hindrance from her. So, in addition to information about environmental pressures on the organization, there was also evidence to suggest that Nicola’s individual difficulty represented something about inter-group issues in the bank; the resistance of traders to operations staff asserting themselves, instead of taking up a traditional passive role. Nicola was stepping into the middle of tensions associated with the way in which investment banks manage the anxiety associated with ‘gambling’ with other people’s money. They make an organizational split6 between those taking risks and those managing them. In being reminded about the risks, the traders might feel infected with anxiety that would make it impossible to act with the usual daring, so they might wish to resist and push the anxiety back to Nicola and to Operations. This might contribute to her ‘poor performance’. A further dimension was that Nicola was one of the few women at her level in the bank. There were no women at her level amongst the traders. So they had little experience in dealing with senior women as well as a lack of experience of women in Operations acting assertively. Their expectation that Operations should act passively might have been strengthened by the expectation that women should or do act more passively than men in the bank or in life generally. Unfortunately, Nicola felt she could not explore this with people directly because gender issues were not talked about openly in the bank. This was because of the fear of saying something discriminatory, following some high profile court cases involving sexism in investment banking. Political correctness in the bank, due to fear of more litigation, made any reference to gender a taboo subject7 .The last point is about the personal relevance for Nicola of the issue of asserting herself with authority figures. She had a difficult upbringing with strict parents who would often punish her for mistakes she made. She described herself as afraid to assert herself with authority figures for fear of the consequences if she got it wrong. She thought she definitely took these feelings from childhood into meetings at work with senior people. Usually she was able to manage her anxiety in these situations but, in meetings with traders, I would suggest because of the organizational dimension with its special ingredient of inter-group tension, Nicola was pushed into incoherence and poor self- presentation. Once we had explored Nicola’s issue in these ways8, she saw that there were actions she could take to help herself, both individually and organizationally. Individually, she could prepare herself differently for the meetings now she understood that she made the traders anxious with her attempts to assert herself; this was quite a new perspective for her. She would need to think about how she could present her ideas in a more collaborative and less challenging way. Organizationally, she checked with other vice presidents about their experience in similar meetings. She discovered that they too, and especially women, had parallel problems. In fact, colleagues thought the traders did not know about the policy of a change of approach in Operations. The vice presidents in Operations decided to meet formally as a group, which had not happened before, to plan how to tackle their shared problem, with a view to an approach to the Head of Operations. The aim was to promote discussion across the bank as a whole about whether the new approach was working and how it should continue with effective support from traders. As a result of the changes Nicola made in her approach to the meetings, her performance improved greatly. The vice presidents group was also able to stimulate a wider discussion across the bank and involving traders about the policy change, with the result that business unit meetings became much longer, at times more conflictual, but also more collaborative. Since promotion crucially depended on recommendations from traders in the business unit, this was important for Nicola’s future. She was promoted to Director later that year. Subsequently, traders began to ask for coaching for the first time, which I would tend to see as the result of their experience of greater personal anxiety. This could have been because the management of task anxiety was now more shared across the organization, rather than being split and only managed by Operations where Nicola worked.This example illustrates how it is possible to help the client read individual experience organizationally and help him or her to arrive at solutions which not only deal with their own ‘problem’ but also impact on the organization in positive ways. Nicola was able to use the meetings with the coach as a ‘third party’ to negotiate a different relationship between herself and the organization. It was also possible to help the organization become aware of the need for change in the way it operated: Nicola was able to engage with the organization via her meetings with her peers and this resulted in wider organisational changes. This raises the question, which will be dealt with later in this chapter, of whether and how the coach could directly intervene to bring about change in the organization. Now I would like to turn to explore in more depth the concept of ‘the organization-in–the-mind’. THE ‘ORGANISATION-IN-THE-MIND’ In ‘Setting the Scene’, I referred to two ways in which the organization is present in the discourse between the client and the coach; as an internal reality, or an internal object in the mind of the client and as an external reality independent of the coach and client. In this section, I would like to turn to the first of these two ways in which the organization is present in coaching as the ‘third party in the wings’. The concept of ‘the organization-in-the mind’ or organization as an internal object was originated by Pierre Turquet and developed by David Armstrong and colleagues at the Grubb Institute (Hutton, Reed and Bazalgette, 1997) and by David when he joined TCS (Armstrong, 1995). He defines it as ‘not the client’s mental construct of the organization, but rather the emotional reality of the organization that is registered in him or her, that is infecting him or her, that can be owned or disowned, displaced or projected, denied ... that can also be known or unthought.’ This experience becomes the material of coaching as it is discussed by the client with the coach and the layers of meaning, conscious and unconscious become apparent. In this definition, emotional experience is seen not as the property of the individual or individuals but ‘emotional experience that is contained within the inner psychic space of the organization and the interactions of its members – the space between’ (Armstrong, 1997). This is akin to the notion of counter-transference from psychoanalytic work but needs to be re-construed in that what is evoked in the consultant or coach is some element of his or her own ‘organization-in-the-mind’ in terms of the organizational setting in which the coach works or has worked over time. Other layers of this complex picture which may become important include the coach’s ‘organization-in-the-mind’ of the client; and the client’s ‘organization-in-the-mind’ of the coach. One way of reading the emotional experience of the client in the organization (from, for example, Jaques 1989) would be that this represents an enactment of the stresses and strains of organizational life and is ‘extraneous noise’ connected to individual or group pathology, a side effect of defective structures or processes in the organization. And that, to understand and work with these better, the coach needs to learn about the patterning of individual and group behaviour under stress; also perhaps that the work of the consultant should be focused on recommending different structures and processes which ‘do away’ with ‘dysfunctional’ emotions and behaviour. There would, for example, be various structural solutions to the need to pay more attention to risk management in the investment bank, of which the creation of business unit teams was one example, with its consequences for Nicola and her colleagues. This is perhaps the explanation for the re-structuring fever that afflicts organizations from time to time. No doubt some organizational problems which create concomitant negative emotional experience and dysfunctional behaviour in its members can be helped by changing structures and processes, but the argument here is that there is something more pervasive or constitutive of organizations that explains the emotional experience we feel and see in our clients. This could be thought of as its primary process, ‘not its aim, but rather something without which none of its stated aims were likely to be achieved’ (Armstrong, 1995) In the example of the investment bank, one take on the ‘heart of the transformation process of the organization’ (Armstrong, 1995) might be the risky business of gambling with other people’s money. And the emotions of fear, greed and excitement tied up in this, and registered in Nicola and in me as she told me her story, is the primary process or daily stuff of organizational life in investment banks, however this is structured or processed by traders or Operations. At that point in time, the issue seemed to be Nicola’s self-confidence, just as, in investment banking world-wide, there was also a larger scale crisis of confidence. It was as if the lack of confidence in the system had got into Nicola because of her personal valency for feeling this way (Bion, 1961). This is something to be understood, acknowledged and managed, and, where possible exploiting its creative potential; rather than something to be avoided, denied and structured out, which I am suggesting is a useless pursuit. Over the years, and influenced by pressures from society, the marketplace and other factors, the primary process finds various means of expression which impact on individuals and groups in various ways mediated by their own constraints, opportunities and valencies. In the case of Nicola, her ‘personal problem’ was simultaneously an expression of individual, group, inter-group, wider organizational and societal turbulence, only some of which she and I could work on, either directly or indirectly. It had its own distinctive flavour imparted by the ‘organisation-in–the-mind’ or our minds as we tried to read together the primary process of the organization, starting with her individual experience. It is not always possible to capture the ‘organisation-in-the-mind’ of clients so clearly as with Nicola; in others, it emerges fleetingly or haltingly or not very much at all. One might wonder why this is the case; what is it about these organizations which means that they register so patchily in the minds of their leaders? What might this mean about the organization, or its environment, or the work group or the individual in question? In other cases, it is quite a quite clear and distinctive flavour. In order to illustrate this, I will describe three examples of the ‘organisation-in-the-mind’ of clients in very different organizational settings and how this was used in my work with them.

Case example 2 Ian is a senior manager in a food manufacturing company and the issue he brought was about developing a greater capacity for strategic thinking. He needed this to progress to the next level in the company. He was highly intelligent and competent at his job, which was as a country manager in this global company. He had previously worked for another company in a different industry sector where he had also been very successful. Great things were expected of him in terms of progressing up the hierarchy. His company was, however, struggling in the marketplace and a number of ways of reorganizing its work were in play at the time. Over a series of meetings, Ian arrived each time looking stressed and complaining of overload and not being able to think. At the same time, he seemed excited about his relatively new job. He described panic and initiative fatigue in the company and of having 500 emails in his in-box and never being able to clear them. He was becoming increasingly focused on detail and operational issues as things became more and more chaotic in his work environment. I found myself feeling confused and not knowing what issue to help him to focus on, as well as anxious that there might be something I was missing in all the detail. I found myself wanting to provide solutions for each of his many operational problems. And yet this was not why he wanted my help. Then I found myself asking, ‘Why does the organization need to operate in crisis mode and appear not to take any time to think things through?’ It was important to be able to reflect on my experience in the room with Ian since my feelings appeared to mirror his experience. This is often the first clue to the organization-in-the- mind of the client. In the mean time, I had visited his organization to run a team day for another client and had seen bowls of company products, sweets, on meeting tables in their offices; and how people grazed on them throughout meetings. When I commented on this, one staff member said, jokingly, “it’s mother’s milk!’ He seemed to be suggesting that they were feeding themselves with the products and perhaps values of the company as a kind of instant gratification or perhaps reassurance. At the beginning of the next meeting, Ian talked about the scrapping of the latest strategic plan developed by outside consultants. And of the teleconferences with his boss, who was delivering a bewildering onslaught of instructions, each duplicating those he had been given before or countermanding some previous initiative. He described the organization as having a ‘hand- to- mouth’ existence and, at the same time, how good everyone was in a crisis. This was interesting because it echoed the ‘hand to mouth’ behaviour observed in the team meeting. I shared my observations with my client. This led into a discussion of how the organizational task of meeting the basic need of hunger, or even greed, the raison d’ etre of a food company, had perhaps got into the way the organization worked. This was reflected in the tendency to be in crisis intervention mode, rather than in reflective or planning mode. We then discussed the difficulty the organization as a whole apparently had with strategic thinking. We concluded it was not just Ian’s problem. In reaching this point, Ian realized it would be very difficult for him to develop strategic thinking, as he had originally construed it, in this organization . We then discussed how strategy did in fact get decided upon in the company, as it undoubtedly did, however chaotic it appeared, and Ian went away with the resolve to find out about how it was done- so we could work on a reframed notion of what he needed to do to progress in this company.This example illustrates a number of things; firstly that the data one is drawing upon to develop one’s thinking and that of the client comes from a variety of sources- what the client says and does not say, how they look and seem to feel, how you feel and what you find yourself saying or doing, observations outside coaching sessions especially if you can visit the organization and so on. Metaphors, images, dreams, drawings – all help to reveal the ‘organisation-in-the mind’. Some clues arrive as gifts- like the sweet bowls or metaphors like ‘hand to mouth’ and others can be engineered, for example by asking the client to make picture of themselves in their organization in their role; or by asking the client to describe a dream or day dream. There is a feeling of evidence mounting until the right moment to engage with the client emerges.

Case example 3 This next example concerns a comprehensive school in a deprived part of the UK and the coaching was with Peter, the head teacher, and his deputy head teachers. This school was very challenging in that it had many students with difficult behaviour and great learning needs. Working as a teacher at the school was demanding but the staff group was loyal and many had been there a very long time. The leadership of the school was effective and standards were improving but the school was constantly under external pressure to achieve higher targets. The topic about which I heard the most from all three clients was about conflict in the leadership team, which they led and of which they were also members. This conflict was of a particularly nasty personal kind and the original point of conflict usually concerned different ideas about how to lead particular projects within the school. Sometimes it involved talking about members of the team behind their backs;sometimes there were rows in the corridors. There were often threats to walk out or resign. Most of the rows were partly secret in that others were not supposed to know about them and could apparently not be discussed in the team as a whole. I would hear about them from various perspectives, including victim and perpetrator, when the rows involved my clients. I felt uncomfortable, worried about my capacity to hold the material confidential and of the possibility of a destructive breakdown in relationships at the top of the school. When I first heard about these rows, I was also surprised as these professionals seemed thin-skinned and the arguments so like the arguments of the adolescents they were teaching. I also heard about rows between teachers elsewhere in the school. The conflict seemed to be both rife and normal. At the same time, in visiting the school where the coaching took place, I could see that relationships between staff and students seemed excellent and of mostly of a very friendly nature. I would often meet one of my clients just as they would finish a supportive conversation with a student, to be followed by the beginning of our meeting, the first few minutes of which would consist of a tirade about another member of the leadership team. It seemed as if the good relationships with students came at the price of difficult relationships with adults in the school. Then it became clear that Peter and his deputies’ identification with the students needed to be strong in order to effectively take up their leadership roles in the organization. In other words, in order to be followed by students and staff in a challenging environment, the leadership team needed to get close to their followers. This included displaying personal vulnerability, rather than distance. This was a learning institution so all involved had to show a need to learn which was a vulnerability in itself. This seemed to be the key feature of the primary process of the organization – managing the vulnerability involved in learning. Vulnerability, together with the aggression and sexuality the students were learning to control, proved an unstable cocktail that the head, deputies and leadership team dealt with on a daily basis. The rows amongst members of the leadership team appeared to represent an expression of vulnerability, identification and stress relief all at the same time. I took a risk in feeding back my thoughts on the ‘organization-in-the-mind’ to Peter, with the result that he felt it would be useful if I shared them with the leadership team as a whole and helped them to think about how they could use team meetings to share and work at some of the feelings that otherwise spilled over into rows. These team meetings facilitated by me became a regular event in the school calendar and, whilst the rows still occasionally take place, the team as a whole is taking a much more active collaborative role in sharing the leadership task of managing vulnerability, including the difficult emotional work that goes with it. This example is interesting in that it shows that data about the ‘organisation-in-the mind’ can come from a variety of sources in the organization if one is working with more than one coaching client in that organization. This does raise issues of confidentiality which need careful consideration (see below under ‘Engaging with the Organization’) but the overall advantages to the organization of the coach being able to feed back themes from the coaching to assist organizational development were the reasons for the school choosing to use one coach to work with all three clients. It again emphasizes how important it can be to have direct experience of the client’s organization, as in my observation of the relationships between staff and students at the school because the coaching took place there.In all three case examples I have described so far, what might be described as the ‘emotional life of the organization’ (Huffington et al 2004) had considerable impact on the individuals concerned, giving a frame and meaning to the issues they brought. These were not emotions that could be ‘structured out’ but needed to be properly understood and managed, making the most of their creative potential. It was possible to tap into this via the ‘organization-in-the-mind’ of the client alone, in the case of Nicola, as well as via direct contact in their organizations, in the case of Ian and Peter, respectively. I would now like to turn to a consideration of the layer of meaning around the organization itself, the current context of organizations in general in the first decade of the 21st century, and how this impacts on the coaching process. THE CURRENT CONTEXT IN ORGANISATIONS The growth in the popularity of coaching for those in leadership roles in organizations in the last 10 years has been remarkable. This can be explained in part by the dramatic changes in organizations in this period in all sectors of the economy. There has been extreme turbulence created by

- the revolution in information technologies and the transmission of knowledge

- globalisation of markets and hence competitive pressures

- increasing levels of risk created by these changes

- changing social and cultural patterns – in families and between generations; in attitudes towards gender and race; and in the concern about work /life balance

- ecological awareness and sensitivity

- wider issues of social responsibility

- economic and political restructuring, for example in Europe

- customerisation and an increasing emphasis on consumer or client sovereignty

- the emergence of a contract culture, especially in the public sector, tied to rigorous and imposed criteria of accountability (Huffington et al, 2004)

Associated with these changes are corresponding shifts in the structuring and patterning of organizations. Organizational boundaries, both internal and external are increasingly fluid, internal structures and roles less clearly defined and conventional hierarchies less evidently relevant. Mergers, strategic alliances and partnerships have become commonplace. There has been a growing preoccupation with the language of vision, mission and corporate values, ownership and ‘empowerment’, alongside the harder edge of ‘outsourcing’, ‘downsizing’ and ‘target-setting’. Within the business world and elsewhere, stable work groups are being replaced by project, sometimes virtual, teams on short-term assignments cutting across traditional professional and positional boundaries. An emphasis on innovation and creativity rubs up against the pressures on delivery and results (Cooper and Dartington,2004).

The impact on those in decision-making roles has been to stress the leadership as opposed to management component of their roles. The changes in organizations appear to have fundamentally ruptured the relationship of the individual to the organization and one of the leader’s new tasks is to focus on negotiating the psychological contract with followers, as this can no longer be assumed (Obholzer, 2004). A more personal and laterally distributed version of leadership has emerged which can be felt to be more personally demanding (Huffington, James and Armstrong, 2004). At the same time, the emphasis on performance and targets can lead to a persecutory environment in which creativity struggles to flourish. It could once be said that the organization contained the individuals within it through the management of boundaries, systems and processes (Miller and Rice, 1967) However, despite the drive towards better performance, there is now a sense of a lack of, or abdication, of management and, hence, a lack of containment, safety and support for people in organizations. Individuals can thus be said to contain the organization within themselves, rather than the other way around. Employees have to manage their own careers, decide their own development plans, organize personal support for themselves via coaching, mentoring and other leadership development; yet they may still look to the leader of the organization to provide this sense of both containment and inspiration (or what has been called ‘pro-tainment’ by Huffington, James and Armstrong, 2004).

The person element of leadership thus appears more important than role or system (in the person/role/system model mentioned earlier) and there is a relative absence of the mediating concept of role in the individual’s experience of his or her encounter with the organization, if my coaching clients are representative. This perhaps accounts for the popularity of the idea of ‘emotional intelligence’ (Goleman, 1998) as leaders need to capture the hearts and minds of the individuals in the organization rather than being able to rely on loyalty, deference or hierarchy to get things done. There tends to be a relative avoidance of the team or group dynamic, despite the need to work in groups, especially because of the reduction of face-to-face contact between people working together across the globe, often virtually. Therefore there is a sense of no organization or system that can be relied upon. There is then a danger that leadership becomes fragmented.

Coaching itself could paradoxically compound the problem if each director is getting his or her support from an external coach as a substitute for genuine connectedness across the team or organization. Organizations seem to be struggling to find the kind of relatedness they need to do business and which can foster growth and innovation. The issue of life/work balance seems not to be so much about the volume of work or the need for flexible work patterns but about the psychological intrusiveness of the organization upon the individual and the need to limit it. The leader has to decide where to draw the boundary between the person he or she is at home and the person he or she brings to work, as this is now no longer clear.

In fact, one could almost get to the position that leadership is so difficult as to be impossible because of the high expectations, personal exposure and the likelihood, or perhaps inevitability of failure, judging by the fate, for example, of football managers. The average longevity of Chief Executives is now only two or three years, which is barely long enough to implement a change programme. There is a great deal of questioning, challenging and criticism of leaders in the media and in organizations. It appears almost impossible for leaders to lead and many are deposed and replaced by new ones who are soon criticized and challenged. There literally appears to be an intolerance of leadership. At the same time, there is a great deal of rhetoric about leadership and a plethora of leadership development initiatives in all sectors of the economy. It is as if there is a longing for leadership that no one can fulfil.

It seems that the leader is now being thought of as an individual taking power to him or herself in a hierarchical way, rather than acting on behalf of the organization or system in taking up the leadership role or function or state of mind. It is possible to see that people in organizations are tending to operate more as individuals, or perhaps pairs, in survivalist mode, rather than being able to connect in a wider way to achieve things as a system, where necessary trusting others to act on their behalf. The concept of the organization as a system of interconnected parts in fact appears absent from the way people think about getting things done. This tends to lead to a state of affairs in which the collaboration needed for creativity and development is missing. People seem to be living in the present and depending on themselves; a kind of feral existence in which leadership means very little. It is what one client called ‘a post leadership situation’.

The popularity of coaching suggests that leaders are looking for a creative partnership in their relationship with a coach to help release them from the isolation and frustration they experience in their leadership roles. Amongst other issues, the challenge appears to be to help these clients develop the kind of relatedness in their organizations which will allow creativity to flourish, rather than encouraging a split –off outsourcing of support. A pairing with a coach seems to create a transitional space, in the absence of a clear concept of role, which can allow the client to negotiate a new relationship with the organization, dealing with their feelings of dependency, wish for a fight or to avoid conflict or leave. In this sense, the coach is a transitional object for the client . The relationship can be represented as in the diagram shown at left. This diagram, in an interesting counterpoint to the Miller and Rice diagram in the introduction to this chapter, shows show the ‘coach’ can replace ‘role’ as a mediating variable between the ‘individual’ and the ‘organization’. This means helping the client to turn back to the organization rather than away from it by working with the client on improving relationships with bosses, colleagues and direct reports in service of the client’s leadership and management tasks. This provides another reason why keeping the organization in mind is so important. A concern about coaches working as individual freelancers is that they may be disenfranchised or disillusioned members of organizations and may be seeking to regain influence in organizations from the outside via coaching its leaders. Therefore they may not be able to assist their clients to genuinely engage with the organization in a collaborative way. CHARACTERISTICS OF COACHING CLIENTS AND COACHING RESPONSES Characteristics of Coaching Clients It is clear from the perspective outlined above on the external context around organizations, that clients come into coaching with issues connected with this turbulence around them. The organizations in their minds are fragile and fragmented places. Put another way, what they bring seems to center around the development of confidence in an environment where there is little confidence in the organization. An appreciation that an experience of vulnerability at a personal level could be seen as normal and based on the reality of organizations today can be a huge relief for the client who may come feeling that they are just not up to the job. In fact, over time, this experience of vulnerability, possibly easier for female leaders to own up to (Coffey, Huffington and Thomson, 1999), can become a valuable indicator of the current state of the organization if the leader can learn to ‘read’ it as emotional intelligence (Armstrong, 2004). Paradoxically, an important role for a coach then is to be able to help the client to value and learn from their experience of vulnerability. And to help leaders to change their behaviour while not feeling confident, entering their ‘risk zone’, but feeling confident as a result; or perhaps helping leaders to learn to behave like a confident person in order to inspire others to have confidence in them. (Sandler, 2003). Broadly, clients seem to be bringing the following groups of issues into coaching:

- Anxiety connected to an experience of vulnerability, as above, as well as ambivalence about having a leadership role, partly reflecting the ambivalence people seem to have about leadership- longing for it but hating it too. Clients may need help in dealing with others’ idealization of them in the leadership role as well as denigration, its inevitable bedfellow.

- Difficulties with the public performance element of a leadership role, such as making presentations, motivating teams and unstructured social interaction with clients, stakeholders or colleagues.

- Getting things done using directive styles of leadership which are so unpopular in these days of inclusivity and empowerment; and due to the increasing fear of litigation from disgruntled employees. Many coaching clients want help in dealing with managing poor performance in their staff.

- Dealing with overwork and being bombarded with tasks and information. Clients want help with time management and filtering what might be called ‘toxic waste’ coming over the organizational boundary. They may need support with developing a critical and reflective approach to things they are asked to do, instead of being over- reactive (Obholzer, 2004).

- The tendency to avoid relatedness and delay in dealing with uncomfortable relationship problems especially conflict; also the wish to avoid tackling organizational politics.

- Leaders often seem to have difficulty letting go of the operational and technical parts of their role that got them the job in favour of a more strategic approach. They may need help with delegation and sharing or distributing leadership as well as dealing with the differently patterned organizational dynamics that result from this. (Huffington et al, 2004).

- Risk-taking is often difficult for leaders who are feeling fragile; yet it is essential to move the organization from survivalist mode to creative development.

- Leaders new in role often need help to think more broadly than the specific function they may have led previously, so they can think about the whole organization and the systemic ripples between its constituent parts and with the environment around it. The coach is, in a way, helping the leader to develop the ability to consult to his or her own organization by improving his or her systemic thinking.

Listed below are some specific case examples of the general areas described above.

- A senior manager in the public sector, who is intellectually brilliant and completely devoted to his job, is unable to confront poor performance and deliver bad news, leaving it too late or relying on others to do this for him. As a result, several staff have taken out grievances against him. He comes into coaching for help with the stress this is causing him .

- A senior partner in a professional services firm is not being admitted to the elite partner group, because he tends to get into conflicts with his peers and will not share work with them. He also can’t see the need to understand and manage organizational politics. He comes into coaching for help with how to get the promotion he is being denied.

- A high- flying young woman leader in a manufacturing company spends no time on networking in the organization and is not well known to the level above her. She is seen as too competitive and territorial about her own division. She comes into coaching having been told she will not progress in the firm, as she wishes to do, unless she can become more ‘corporate’ in her behaviour.

These three examples illustrate three broad areas in which coaches are often asked to help;

- ‘fixing problem people’

- helping a client to make a transition from one career step to another

- learning skills of leadership (Peltier, 2002)

Coaching Responses

The overall framework around coaching that allows the coach to keep the organization in mind is a process consultancy approach (Schein,1988) or ‘combining coaching with consulting’ (O’Neill, 2000, Peltier, 2001, Kilburg, 2002). This means that the coach begins with the issue that the client has brought but attempts to work with the client to understand and resolve it within the broad systems framework described above. The aim is for the client to be able to develop a contextual perspective on an issue that may feel very personal, so that eventually they can appreciate the relative contributions of the organization in them as well as them in the organization. Specific techniques borrowed from family therapy can help the client to develop this wider or systemic perspective, for example the use of reflexive questions (Campbell, Draper and Huffington 1988, 1989, Hieker, 2003). The use of these kinds of questions can bring about change in themselves and is known as ‘interventive interviewing’ (Tomm, 1987,1988).

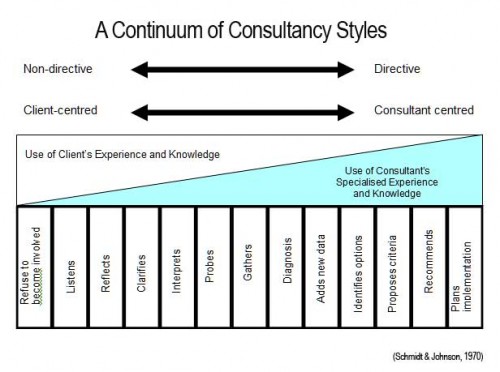

The coach and client would then carefully work through the stages of the consultancy process based on an action research model as in the diagram below (Huffington et al 1997). This perspective is a good example of the fusion contained in the title of this book ‘Coaching from a Systems-Psychodynamic Perspective’.

This is what we at the Tavistock Consultancy Service have called a ‘process coaching’ approach. For different clients, there would be varying emphasis on the three main elements of the coaching response described by Sandler (2003) of extending insight, managing emotions and developing behavioural strategies. This could involve giving advice and being directive at times if that is what the client needed to help them move on in their development. It is, however, a subtle and complex process that is different from both organizational consultancy and psychotherapy and counseling , from which professional fields executive coaches are often drawn. It requires a blend of skills from both fields and a mind set that is different again. TCS provides in-depth training in this approach which requires careful development and ongoing supervision.

The emphasis on achieving behaviour change and outcome in terms of better individual performance in role or better overall organizational performance provides an obvious practical link between coaching and the organization via the results of coaching. Organizations, which use coaching to develop their leaders are concerned to show that coaching is a worthwhile investment for the organization as well as for the individual (e.g.; Rolph, 2004). Clients enter the process, be it organizational role consultation or executive coaching, not primarily to gain more or a deeper understanding, but to improve something, change something, become more effective themselves and/or enable the organization and those who work in it to become more effective. Understanding for most clients is valued as a prelude to action, or perhaps no action. Moreover, there is a real sense in this work, as against, say individual psychotherapy, in which, just as understanding may be the prelude to action, action is the test of understanding. In other words, it is through an iterative process of gaining understanding- testing understanding in practice- and using the results to test one’s understanding- that the process really takes off. Coaching could thus be seen as a kind of guided or facilitated action research. One of my clients described it as ‘guided self-exploration’.

Mary Beth O’Neill (2000), emphasizing the need to clearly link coaching to the organization, describes the essentials of the task to be-

- bringing a results orientation to the leader’s problem, staying focused on how the leaders can make the organization successful

- partnering the client to greater effectiveness

- helping the leader to face not avoid his or her specific leadership challenges

- turning the leader towards his or her team (2000 p 7-8)

Depending on the circumstances, the coach may work solely with the individual client and his or her organization-in-the-mind or may have the opportunity to engage directly with the organization in various ways. I would now like to turn to some of the issues connected with doing so.

ENGAGING WITH THE ORGANISATION

In this section, I would like to turn to the second of the two ways in which the organization is present in coaching as ‘the third party in the wings’; that is as an external reality with which the coach can engage directly. It is another demonstration of helping the client develop their relatedness to the organization rather than engage in coaching as a split-off or privatized development activity.

Whilst working directly with the client’s organization provides many opportunities to enhance the coaching outcome, there are a number of issues the coach needs to consider carefully.

Contracting Issues

The framing of the initial contract with the organization and with the client is crucial to being able to keep open the possibility of working directly with the organization. Even if the coaching does not involve explicit contact with the organization thereafter, many organizations, especially large corporates, set up the contract for coaching via a meeting between the client, the client’s line manager and the potential coach. This is often so that the line manager can set out the aims he or she has for the coaching based on the client’s development needs, sometimes identified by 360 degree feedback assessment processes in the organization or a personal development plan. This line manager then legitimizes payment for the coaching. Sometimes this contracting and legitimizing process may additionally involve a representative from the human resources, training or development arm of the organization. A similar meeting between client, line manager and coach can sometimes be required at review points and at the conclusion of the coaching contract. The important issues here are:

- The coach needs to be able to take up his or her authority as a coach to work on the client’s agenda whilst staying close to the needs of the organization. There is a kind of double contracting needed- once with the organization, and again with the client, in the light of the organization’s needs. Clearly in the triangular relationship between the client, coach and organization, there is potential for divergence and splitting. This might, for example, happen if the organization is using coaching as a means of controlling a problematic individual and attempting to use the coach to collude in this process. There is a danger of the coach being ‘set up’ by the organization and failing either the organization or the client. For example, I was once asked by the trading arm of an investment bank to work with a male client who had been accused of bullying. It was made clear to me that if he did not improve his behaviour through a set number of coaching sessions, he would be sacked and so would I! The issue I then began working on with the angry client, who did not want to be coached, was whether it was possible for us to contract for work together in this coercive, even bullying, organization. Fortunately, using this frame in my negotiations with the client allowed us to work at the reasons for his anger and that of the organization. The outcome was that he decided to leave the organization of his own accord. Whilst always holding open to myself the possibility of refusing to agree a contract if I felt my authority as a coach was compromised, I have never actually needed to do so.

- The second issue is about confidentiality, as the line manager can feel legitimized, by virtue of a contract with the coach, to ask the coach for progress reports on the client without his or her knowledge. It is important in the contracting stage to attempt to rule this out as a possibility further down the track by telling the client and manager together that any progress reports for the manager will be created by the coach and client together, not by the coach alone. Even if the manager does contact the coach for a report, he or she would need to be reminded of the original agreement, as this is essential to the integrity of work with the client. I have, however, found it useful in these circumstances to ask the manager what has happened in the organization that has made him or her want feedback about coaching progress now, as the response to this question can yield valuable information both about the client and about the organization. It can often be tricky for the coach at this point to make a judgement about what is in the best interests of the client and organization and this needs to be decided on a case by case basis with the help of the external supervision that all coaches need.

- Lastly, there is the issue of evaluation, which is becoming increasingly important as part of the professionalisation of the field of coaching ( Berglas, 2002, Rolph, 2004) Organizations are increasingly asking coaches to give evidence of the effectiveness of their methods and will often ask how the success of coaching an individual client will be assessed. A coach working within a process consultancy framework should not have too much difficulty with this, in that negotiation of methods of evaluation would usually be inbuilt at the contracting stage as expectations of the outcome of coaching are discussed with the client and their manager, if involved. During the first few sessions, the coach would work carefully with the client to articulate their goals from coaching and, where possible, specify these in behavioural terms, even though goals will shift and change over time. For example, if the client says they want to become more confident, the coach would ask ‘How would this show?’ ‘In which situations?’ ‘What difference would this make to your leadership?’ ‘ Who would notice?’ and ‘How would they show that they had noticed?’ And, at review points, the coach would remind the client of the last goals set and the expected behavioural indices of change in order to evaluate success and set new goals and new indices.

Interventions in the Organization

If one has a background as an organizational consultant and is extending this into executive coaching, the idea of engaging directly with the organization is not an unusual thing to do. However, if one has a background as a psychotherapist who has previously focused on the inner world of the patient or client, this can feel like breaking a taboo. My experience is that it can be enormously liberating and illuminating to have direct experience of the ‘third party in the wings’.

I have used three kinds of intervention:

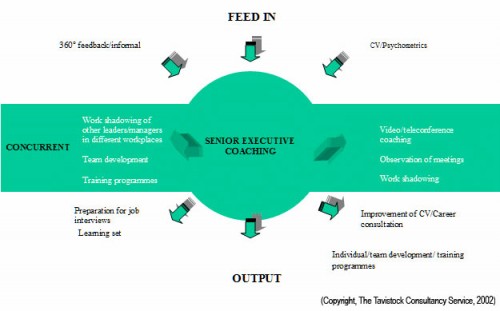

- Additional services to support coaching to the individual. At The Tavistock Consultancy Service, we call this “Coaching Plus’ as in the diagram below (click to enlarge). These additional services include 360 degree feedback interviews with direct reports, peers, bosses and other stakeholders the client works with; observation of the client in the workplace; team coaching.

- Feedback to the organization about themes from coaching, where more than one client is involved

- Working with the whole organization from the platform of coaching.

I would like to take you through a practical account of using these modes of intervention, some of the opportunities and dilemmas they present and illustrate how I have managed them.

Additional services to support coaching

Whilst this does not happen with every client, for some who are feeling particularly stuck or who seem lacking in feedback about their impact, progress or potential in the organization, it can be very helpful to gather additional data about them. The added benefit is of the active involvement of a neutral third party, the coach, through which members of the organization can communicate about the individual and about the organization. Then the coach is no longer the ‘third party in the wings’ or hidden, from the perspective of the organization.

360 degree feedback interviews

These are so called because they offer the client the possibility of feedback from multiple or all round perspectives. They can be conducted by the coach face to face or by telephone and set out to gather feedback about the client in specific areas chosen by him or her. The responses are confidential and the feedback given to the client anonymously. In carrying out the interviews, the coach can test out a variety of hypotheses about the organization and the relationship between the client, the organization and the issues brought. If it is possible to pose systemic questions, for example, ‘Why do you think your organization fails to give praise and appreciation?’, the interviews can shift thinking in those being interviewed so have the potential for greater mileage. The impact of doing these interviews can be powerful in that members of the organization are alerted to the client’s need and wish for personal development and become subtly co-opted into the process, becoming monitors or evaluators of progress. They can be interviewed again at a later stage to tap into this. It can also create an opportunity for the client to relate to the respondents differently following the interviews when new conversations have taken place via the third party involvement.

Observation of the client in the workplace

I have found this useful when a client is having difficulties in specific settings or in particular relationships, for example chairing meetings. Whilst others present can feel initially self-conscious about the presence of the coach in the room, this quickly disappears. It is important to clearly contract with all those present and explain about the purpose of the observation, which is primarily to assist the client not to observe others or consult to the team or meeting. It can be helpful to invite them to privately feed back their ideas on the client to you as coach during or after the meeting. Also one can offer to give general feedback about the meeting if requested. A variation on this pattern is ‘real time feedback’ or coaching during the meeting. This entails setting up 20 minute breaks at regular intervals throughout the meeting to share feedback on specific behaviours.

For example, I was once asked to help a client be less directive in the team meetings he led as he was trying to be more open, inclusive and to say less but his team still found him overbearing. My feedback throughout the day long meeting was to what extent he was managing to achieve his aims and how and in what ways he could do more, taking account of the team dynamic of which he was not fully aware. In well-entrenched behaviour patterns like those of my client and his team, the disruption of my presence and frequent breaks were needed to create some capacity for them all to reflect on the stimuli that led him to be so controlling and for others to let him. The relief of all was apparent at the end of the day and I was subsequently invited to get involved in team coaching.

Team coaching

Clients often ask a coach to work with their team but this request should be viewed with caution. The reason is that working with the client’s team challenges the paired relationship the coach has with the client in various ways.

- It wwill be difficult for other members of the team to trust the coach; they will tend to believe that the coach will see the world and them through the client’s eyes.

- It can be difficult for the coach to challenge the client in front of the team

- The client often has an agenda which is about ‘licking the team into shape’ his or her way, rather than offering a consultation or coaching to the team as a whole. This might be valuable to the team but it might not be experienced that way and a fight/flight dynamic (Bion, 1961) can emerge.

- A different skill set and personal valency ( Bion, 1961) is involved in team coaching which involves an understanding of group dynamics and group facilitation; it is not simply a matter of scaled-up one- to- one coaching.

Thus a very effective coach can be rendered ‘incompetent’ working with the client’s team. I usually ask a colleague in my team to take up team coaching for my client and we then work together on the issues involved. I have found that this releases feedback about the client and the organization that is valuable in the coaching; and often the colleague continues to act as a resource to the team and more widely in the organization.

Giving feedback to the organization

If one is working with more than one senior client but not the boss in an organization, or if the coach is working with colleagues coaching other clients, it can be very useful to feed back some of the themes from this work in the organization, without breaching individual confidentiality and with the permission of the clients concerned. Some organizations do not ask for or welcome this, whereas for others it can be part of the coaching contract. I would see the lack of interest in some organizations as connected to the way coaching can be seen as an ‘executive perk’ and a cut- off or privatized form of personal development. Even in these circumstances, I would make a big effort to find opportunities to feed back on organizational themes. The reasons would be two-fold:

- So as to understand the organization better in order to enhance the coaching of individuals

- To give feedback to the organization that they might not otherwise have and which might enhance organizational development.

For example, I was working with five clients in an investment bank and became aware of shared themes in the work with the individuals that did not seem to be taken up by the organization. The Human Resources department sponsored the coaching but did not have a way of tapping into general feedback on themes from coaching. I asked for quarterly appointments with the HR director. I discovered that, even though he had not sought it out, he was interested in hearing feedback from me as it might help the bank hold on to its high performers who were being coached. I offered feedback about their problems in developing strategic thinking, dilemmas experienced by women in senior leadership roles and difficulties in managing poor performance. This led to the development of specific training modules for senior staff as well as thinking about flexible work packages for men and women. In return, I heard about various aspects of organizational strategy that I had not picked up on from individual clients. It continues to be a valuable interchange that the clients themselves see as a useful channel of communication to the organization through me.

In other situations, where I have been working at CEO and Board director level, I have been able to feed back themes which, potentially impact organizational strategy as a whole.

Working with the whole organization from the platform of coaching

My experience of doing this is that it is usually difficult. Firstly one ideally needs to be working at CEO or Board level to have any impact on the organization as a whole, but, even then, the pairing relationship can get in the way as I have already suggested above (under team coaching). The clients tend to be reluctant to extend or share the one- to- one relationship more widely, except perhaps with their immediate team. This appears partly due to the need they have for exclusive support given the isolation, vulnerability and frustration of the leadership role. My experience is that more extended work is likely to grow from an initial contract, which includes coaching amongst other activities, and then coaching itself facilitates the development of other forms of intervention. The role can then be seen more clearly as organisational consultant, or resource to the organization as a whole, rather than just to an individual leader.

For example, I had an initial contact from a head teacher about help for an under-performing senior management team, following a negative inspection result. When I met the head teacher, he seemed lacking in confidence in his own ability to lead the school’s recovery and he said the senior management team morale was low. The first phase of my work was a development needs analysis of the team. I made several recommendations about team development, including coaching for the head teacher. From this and over time, a range of other interventions developed; coaching for other members of the team; team coaching; assistance with selection of new team members, including ideas for the interview process; design of and participation in a conference for students; input to business planning . During the next 2 years, the school improved its performance greatly and was assessed positively when it was inspected again. The head teacher and his team were praised for demonstrating good leadership and management. In all this and despite the organizational consultancy frame, my primary relationship was with the head teacher, the person in the ultimate leadership role. All the interventions needed to have reference to his vision for the school. This did not mean that it went unchallenged but this was done in one- to- one coaching. Other staff often sought opportunities to give me feedback on the head’s vision, strategy and behaviour and it was then important to reflect on the meaning of this and ensure that I was not being used inappropriately as substitute management in the organization. At points like these, it was useful to involve other colleagues in the work where my paired relationship with the head teacher would have got in the way, for example coaching one of the deputy heads on his future development into headship; coaching for a very junior member of staff; team coaching for a member of the management team.

CONCLUSIONS: THE CONFIDENT ORGANISATION

In this chapter, I have described executive coaching as a variety of organizational consultancy from a conceptual, practical and ethical point of view. My tendency is to think of executive coaching as the form of organizational consultancy that is currently acceptable to organizations given the current climate of fragility in and around them. It appears that the pairing relationship of client and coach is the kind of relationship that has the most potential for promoting creativity and growth of leaders in organizations. I would say that, in order to help the leader to develop his or her confidence and effectiveness, coaching needs to take account of the ‘third party in the wings’ or organization where the client works. This is so that the client does not use coaching to turn away from the organization to the privatized pairing of coach and client and thus avoid his or her relatedness to the organization. The coach needs to help the client face into it and manage the uncertainties. Then there is some possibility that, in developing the leader’s personal confidence, this will also help to develop a sense of confidence in the organization as a whole. The confident organization is more likely to be able to be creative, take risks, survive and grow in the future.

Footnotes

1 The Tavistock Consultancy Service (TCS) is a unique organizational consultancy unit within a National Health Service Trust in UK. It works to develop organizational health using a systems-psychodynamic framework. Its clients are from the public, private and voluntary sectors. Services include senior executive coaching, top team development, organizational interventions, research and training. Clare Huffington is the current Director of TCS.

2 See also the chapter in this book by Erika Stern

3 See also the chapter in this book by Gordon Lawrence

4 This should equally apply to clients coming from an organization but paid for by themselves, perhaps without the knowledge of the organization; and one might wonder as a first hypothesis what it is about their organization that means that executives privatise their own learning and development. This does not mean that one would not attend to personal distress if it really did seem to be personal, but one would then perhaps be assisting the client to find psychotherapeutic support. This could take place alongside coaching, which fulfils a different function. Indeed, one might say that the coach has, as a goal of coaching, the improvement of the client’s ability to think and act systemically about issues that are initially personal; and indeed part of the coaching task is to help the client to read their emotions in this way, as intelligence about the organization (Armstrong, 2004).

5 All case examples used in this chapter do not concern real clients but are an amalgam of material from a number of clients. Names, details and organizations have been changed to protect client confidentiality.

6They make this split for perfectly sensible governance reasons but I am suggesting here that it also serves a psychological function in the organisation.

7 Of course, it would have been possible to have explored it in many other equally valid ways.

REFERENCES

Armstrong, D (1995) The Analytic Object in Organizational Work Occasional Paper: The Tavistock Consultancy Service

Armstrong, D (1997) The ‘Institution in the mind’: Reflections on the relation of psychoanalysis to work with organizations. Free Associations 7 (41) 1-14

Armstrong, D (2004) Emotions in organizations: disturbance or intelligence. Chapter 1 in Working Below the Surface: The Emotional Life of Contemporary Organizations edited by C.Huffington, D. Armstrong, W. Halton, L. Hoyle and J. Pooley; London, Karnac Books

Berglas, S (2002) The Very Real Dangers of Executive Coaching June 2002 pp87-92 Harvard Business Review

Bion, W.R (1961) Experiences in Groups and other papers; London, Tavistock Publications

Blom, H (2004) Personal communication

Campbell, D, Draper, R and Huffington, C (1988) Teaching Systemic Thinking: London, Karnac

Campbell, D, Draper, R and Huffington, C (1989) A Systemic Approach to Consultation; London, Karnac

Coffey, E, Huffington, C and Thomson, P (1999) The Changing Culture of Leadership: Women Leaders’ Voices: London, The Change Partnership

Cooper, A and Dartington, T (2004) The networked organization. Chapter 7 in Working Below the Surface: The Emotional Life of Contemporary Organizations edited by C.Huffington, D. Armstrong, W. Halton, L. Hoyle and J. Pooley; London, Karnac

Cronen, V, Pearce, W and Tomm, K (1985) A dialectical view of personal change in The Social Construction of the Person edited by K Gergen and K Davis; New York, Springer-Verlag

Goleman, D (1998) Working with Emotional Intelligence; London, Bloomsbury Publishing

Hieker, C (2003) Reflexive questions in a coaching context. Unpublished paper

Huffington, C, Cole, C and Brunning, H (1997) A Manual of Organizational Development: The Psychology of Change; London, Karnac Books

Huffington, C, James, K and Armstrong, D (2004) What is the emotional cost of distributed leadership? Chapter 4 in Working Below the Surface: The Emotional Life of Contemporary Organizations edited by C.Huffington, D. Armstrong, W. Halton, L. Hoyle and J.Pooley; London, Karnac Books

Huffington, C, Armstrong, D, Halton, W, Hoyle, L and Pooley, J (eds) (2004) Working Below the Surface: The Emotional Life of Contemporary Organizations; London, Karnac Books

Hutton,J, Bazalgette,J and Reed, B (1997) Organisation-in-the-mind In J.E. Neumann, K. Kellner,and A. Dawson-Shepherd (Eds) Developing Organizational Consultancy p113-126 London, Routledge

Jaques, E (1989) Requisite Organization: The CEO’s Guide to Creative Structure and Leadership; Arlington, VA, Cason Hall

Kilburg, R ( 2002) Executive Coaching: Developing Managerial Wisdom in a World of Chaos; Washington, American Psychological Association

Miller, EJ and Rice AK (1967) Systems of Organization: Task and Sentient Systems and Their Boundary Control: London, Tavistock Publications

Obholzer, A (2004) Leader- Follower Relations and the Creative Workplace Chapter 2 in Working Below the Surface: The Emotional Life of Contemporary Organizations edited by C. Huffington, D. Armstrong, W. Halton. L. Hoyle and J.Pooley; London, Karnac

O’Neill, M.B (2000) Executive Coaching with Backbone and Heart; San Francisco, Jossey-Bass

Peltier, B (2001) The Psychology of Executive Coaching: Theory and Application; New York, Brunner- Routledge

Pogue-White, K ( 2001) Applying learning from experience. The intersection of psychoanalysis and organizational role consultation. In L Gould, L Stapley & M Stein ( Eds). The Systems-Psychodynamics of organisations. London, Karnac